ARTICLE AD BOX

Zoya Mateen

BBC News, Delhi

Getty Images

Getty Images

The iconic Kolhapuri sandals drew attention after Prada was accused of replicating the design

A recent controversy surrounding Italian luxury label Prada has put the spotlight on how global fashion giants engage with India - a country whose rich artistic traditions have often suffered because of its inability to cash in on them.

Prada got into trouble in June after its models walked the runway in Milan wearing a toe-braided sandal that looked like the Kolhapuri chappal, a handcrafted leather shoe made in India. The sandals are named after Kolhapur - a town in the western state of Maharashtra where they have been made for centuries - but the Prada collection did not mention this, prompting a backlash.

As the controversy grew, Prada issued a statement saying it acknowledged the sandals' origins and that it was open to a "dialogue for meaningful exchange with local Indian artisans".

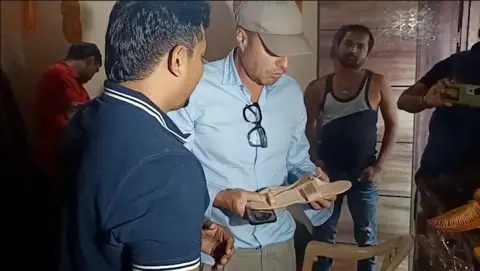

Over the past few days, a team from Prada met the artisans and shopkeepers in Kolhapur who make and sell the sandals to understand the process.

Prada told the BBC that it held a "successful meeting" with the Maharashtra Chamber of Commerce, Industry & Agriculture, a prominent industry trade group.

The statement also indicates that Prada may potentially collaborate in future with some manufacturers of Kolhapuri footwear.

While it's not clear what form this collaboration may take, it's a rare example of a global fashion giant acknowledging that it failed to credit local artisans and the craft it was piggybacking on.

Many big brands have been routinely accused of drawing inspiration from Indian, and wider South Asian, traditions in their quest to reinvent and stay relevant - but without crediting the source.

Earlier this year, spring designs from Reformation and H&M ignited a fiery debate on cultural appropriation after many said that their outfits appeared heavily inspired by South Asian garments. Both brands issued clarifications - while H&M denied the allegations, Reformation said its design was inspired by an outfit owned by a model with whom it had collaborated for the collection.

And just two weeks ago, Dior was criticised after its highly-anticipated Paris collection featured a gold and ivory houndstooth coat, which many pointed out was crafted with mukaish work, a centuries-old metal embroidery technique from northern India. The collection did not mention the roots of the craft or India at all.

The BBC has reached out to Dior for comment.

ANI

ANI

A team from Prada met makers and sellers of Kolhapuri sandals this week

Some experts say that not every brand that draws inspiration from a culture does so with wrong intentions - designers around the world invoke aesthetics from different traditions all the time, spotlighting them on a global scale.

In the highly competitive landscape of fashion, some argue that brands also don't get enough time to think through the cultural ramifications of their choices.

But critics point out that any borrowing needs to be underpinned by respect and acknowledgement, especially when these ideas are repurposed by powerful global brands to be sold at incredibly high prices.

"Giving due credit is a part of design responsibility, it's taught to you in design school and brands need to educate themselves about it," says Shefalee Vasudev, a Delhi-based fashion writer. Not doing so, she adds, is "cultural neglect towards a part of the world which brands claim to love".

Estimates vary about the size of India's luxury market, but the region is widely seen as a big growth opportunity.

Analysts from Boston Consulting Group say the luxury retail market in India is expected to nearly double to $14bn by 2032. Powered by an expanding and affluent middle class, global luxury brands are increasingly eyeing India as a key market as they hope to make up for weaker demand elsewhere.

But not everyone shares the optimism.

Arvind Singhal, chairman of consultancy firm Technopak, says a big reason for the seeming indifference is that most brands still don't consider India a significant market for high-end luxury fashion.

In recent years, many high-end malls with flagship luxury stores have opened up in big cities - but they rarely see significant footfall.

"Names like Prada still mean nothing to a majority of Indians. There is some demand among the super-rich, but hardly any first-time customers," Mr Singhal says.

"And this is simply not enough to build a business, making it easy to neglect the region altogether."

Many big global labels have opened up showrooms in Indian cities in recent years

Anand Bhushan, a fashion designer from Delhi, agrees. He says that traditionally, India has always been a production hub rather than a potential market, with some of the most expensive brands in Paris and Milan employing Indian artisans to make or embroider their garments.

"But that still does not mean you can just blatantly lift a culture without understanding the history and context and brand it for millions of dollars," he adds.

The frustration, he says, is not focused on any one label but has been building for years.

The most memorable misstep, according to him, took place during the Karl Lagerfeld "Paris-Bombay" Métiers d'Art collection, showcased in 2011. The collection featured sari-draped dresses, Nehru-collared jackets and ornate headpieces.

Many called it a fine example of cultural collaboration, but others argued it relied heavily on clichéd imagery and lacked authentic representation of India.

Others, however, say no brand can afford to write off India as insignificant.

"We might not be the fastest-growing luxury market like China, but a younger and more sophisticated generation of Indians with different tastes and aspirations is reshaping the landscape of luxury," says Nonita Kalra, editor-in-chief of online luxury store Tata CliQ Luxury.

In the case of Prada, she says the brand seemed to have made a "genuine oversight", evident from the lengths to which it has gone to rectify its mistake.

For Ms Kalra, the problem is a broader one - where brands based in the west and run by a homogenous group of people end up viewing consumers in other parts of the world through a foreign lens.

"The lack of diversity is the biggest blind spot of the fashion industry, and brands need to hire people from different parts of the world to change that," she says.

"But their love and respect for Indian heritage is genuine."

Reuters

Reuters

Prada's toe-braided sandal - which strongly resembles the Indian Kolhapuri - was showcased in Milan last month

The question of cultural appropriation is complex, and the debates it sparks online can seem both overblown and eye-opening.

And while there are no simple answers, many feel the outrage around Prada has been a great starting point to demand better accountability from brands and designers who, until now, have largely remained unchallenged.

It is an opportunity for India, too, to reflect on the ways it can support its own heritage and uplift it.

Weavers toil for weeks or months to finish one masterpiece, but they often work in precarious conditions without adequate remuneration and with no protection for their work under international intellectual property laws.

"We don't take enough pride and credit our own artisans, allowing others to walk all over it," Ms Vasudev says.

"The trouble also is that in India we have simply too much. There are hundreds of different craft techniques and traditions - each with its constantly evolving motif directory going back centuries," says Laila Tyabji, chairperson of Dastkar, which promotes crafts and craftspeople.

"We bargain and bicker over a pair of fully embroidered juthis (shoes) but have no issues over buying a pair of Nike trainers at 10 times the price - even though the latter has come off an assembly line while each juthi has been painstakingly and uniquely crafted by hand," she says.

And while that continues, she says, foreign designers and merchandisers will do the same.

Real change can only happen, she says, "when we ourselves respect and appreciate them - and have the tools to combat their exploitation".

6 hours ago

14

6 hours ago

14

English (US) ·

English (US) ·