ARTICLE AD BOX

BBC

BBC

A Russian call-up poster urges the local population in occupied Melitopol to "Defend the Motherland, professionally"

A fifth of Ukrainian territory is now under Russian control, and for Ukrainians living under occupation there seems little chance that any future deal to end the war will change that.

Three Ukrainians in different Russian-controlled cities have told the BBC of the pressures they face, from being forced to accept a Russian passport to the risks of carrying out small acts of resistance. We are not using their real names for their own safety, and will call them Mavka, Pavlo and Iryna.

The potential dangers are the same, whether in Mariupol or Melitopol, seized by Russia in the full-scale invasion in 2022, or in Crimea which was annexed eight years before.

Mavka chose to stay in Melitopol when the Russians invaded her city on 25 February 2022, "because it is unfair that someone can just come to my home and take it out".

She has lived there since birth, midway between the Crimean peninsula and the regional capital Zaporizhzhia.

In recent months she has noticed a ramping up of not only a strict policy of "Russification" in the city, but of an increased militarisation of all spheres of life, including in schools.

She has shared pictures of a billboard promoting conscription to young locals, a school notebook with Putin's portrait on it, and photos and a video of pupils wearing Russian military uniforms instead of the school outfits - boys and girls - and performing military education tasks.

Some 200km (125 miles) along the coast of the sea of Azov, and much closer to the Russian border, the city of Mariupol feels as if it has been "cut off" from the outside world, according to Pavlo.

This key port and hub of Ukraine's steel industry was captured after a devastating siege and bombardment that lasted almost three months in 2022.

Russian citizenship is now obligatory if you want to work or study or have an urgent medical help, Pavlo says.

"If someone's child, let's say, refuses to sing the Russian anthem at school in the morning, the FSB [Russia's security service] will visit their parents, they will be 'pencilled in' and then anything can happen."

REUTERS/Alexander Ermochenko

REUTERS/Alexander Ermochenko

After more than three years under Russian control, Mariupol feels "cut off" from the outside world, says Pavlo

Pavlo survived the siege despite being shot six times, including to his head.

Now that he has recuperated, he feels he cannot leave because of elderly relatives.

"Most of those who stayed in Mariupol or returned, did so to help their elderly parents or their sick grandparents, or because of their flat," he tells me over the phone after midnight so no-one will overhear.

The biggest preoccupation in Mariupol is holding on to your home, as most of the property damaged in the Russian bombardment has been demolished, and the cost of living and unemployment has surged.

"I'd say 95% of all talk in the city is about property: how to claim it back, how to sell it. You'll hear people talk about it while queuing to buy some bread, on your way to a chemist, in the food market, everywhere," he says.

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

Most of the homes in Mariupol damaged in Russia's bombardment have now been demolished

Crimea has been under occupation since Vladimir Putin annexed the peninsula in 2014, when Russia's war in Ukraine began.

Iryna decided to remain, also to care for an elderly relative but also because she did not want to leave "her beautiful home".

All signs of Ukrainian identity have been banned in public, and Iryna says she cannot speak Ukrainian in public any more, "as you never know who can tell the authorities on you".

Children at nursery school in Crimea are told to sing the Russian anthem every morning, even the very youngest. All the teachers are Russian, most of them wives of soldiers who have moved in from Russia.

Iryna occasionally puts on her traditional, embroidered vyshyvanka top when she has video calls with friends elsewhere on the peninsula.

"It helps us to keep our spirits high, reminding us about our happy life before the occupation".

This leaflet, in a tree in Crimea, shows a Ukrainian woman in a vyshyvanka defiantly saying "Not yours"

But the risks are high, even for wearing a vyshyvanka. "They might not shoot you straight away, but you can simply disappear afterwards, silently," she declares.

She speaks of a Ukrainian friend being questioned by police because Russian neighbours, who came to Crimea in 2014, told police he had illegal weapons. "Of course he didn't. Luckily they let him go in the end, but it's so frightening."

Iryna complains that she cannot go out on her own even for coffee "because solders can put a gun at you and say something abusive or order you to please them".

Local residents under occupation in Crimea share images of Ukrainian military attacks on Russian targets on the peninsula

Resistance in Ukraine's occupied cities is dangerous, and it often comes in small acts of defiance aimed at reminding residents that they are not alone.

In Melitopol, Mavka talks of being part of a secret female resistance movement called Zla Mavka (Angry Mavka) "to let people know that Ukrainians don't agree with the occupation, we didn't call for it, and we will never tolerate it".

The network is made up of women and girls in "pretty much all occupied cities", according to Iryna, although she cannot reveal its size or scale because of the potential dangers for its members.

Mavka describes her role in running the network's social media accounts, which document life under occupation and acts like placing Ukrainian symbols or leaflets in public places "to remind other Ukrainians that they are not alone", or even riskier practices.

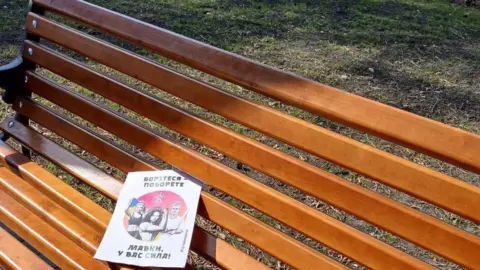

A leaflet on a park bench says the Mavka movement "has the power", quoting the famous words of national poet Taras Shevchenko: "Fight and you will overcome"

"Sometimes we also put a laxative in alcohol and baked goods for the Russian soldiers, as a 'welcome pack'," she says.

Punishment for that kind of act, which the BBC is unable to verify, would be severe.

Russia's occupation authorities treat the Ukrainian language or anything related to Ukraine as extremist, says Mavka.

Ukrainians are well aware of what happened to journalist Viktoriia Roshchyna, 27, who disappeared while investigating allegations of torture prisons in eastern Ukraine in 2023.

Russian authorities told her family she had died in custody in September 2024. Her body was returned earlier this month, with several organs removed and clear signs of torture.

Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Viktoriia Roshchyna was held first in Russian-occupied Melitopol before being moved to prison in Russia

Silent disappearance is what Mavka fears most: "When suddenly nobody can find out where you are or what's happened to you."

Her network has developed a set of tasks for new joiners to pass to avoid infiltration, and so far they have managed to avoid cyber attacks.

For now they are waiting and watching: "We cannot take up arms and fight back against the occupier right now, but we want at least to show that pro-Ukrainian population is here, and it will also be here".

She and others in Melitopol are following closely what is happening in Kyiv, "because it is important for us to know whether Kyiv is ready to fight for us. Even small steps matter".

"We have a rollercoaster of moods here. Many are worried documents might get signed that, God forbid, leave us under Russian occupation for even longer. Because we know what Russia will do here."

The worry for Mavka and people close to her is that if Kyiv does agree a ceasefire it could mean Russia pursuing the same policy as in Crimea, erasing Ukrainian identity and repressing the population.

"They've been already replacing locals with their people. But people here are still hopeful, we will continue our resistance, we'll just have to be more creative".

Unlike Mavka, Pavlo believes the war must end, even if it means losing his ability to return to Ukraine.

"Human life is of the greatest value… but there are certain conditions for a ceasefire and not everyone might agree with them as it raises a question, why have all those people died then during the past three years? Would they feel abandoned and betrayed?"

Pavlo is wary of talking, even via an encrypted line, but adds: "I don't envy anyone involved in this decision-making process. It won't be simple, black and white.

Iryna fears for Crimea's next generation who have grown up in an atmosphere of violence and, she says, copy their fathers who have returned from Russia's war against Ukraine.

She shows me her bandaged cat, and says a child on her street shot it with a rubber bullet.

"For them it was fun. These kids are not taught to build peace, they are taught to fight. It breaks my heart."

1 day ago

14

1 day ago

14

English (US) ·

English (US) ·