ARTICLE AD BOX

Lina Sinjab

BBC Middle East correspondent

Reporting fromSyria

OMAR HAJ KADOUR/AFP via Getty Images

OMAR HAJ KADOUR/AFP via Getty Images

More than 100 people were killed in sectarian violence in a suburb south of Damascus in April

When the gunfire started outside her home in the Damascus suburb of Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, Lama al-Hassanieh grabbed her phone and locked herself in her bathroom.

For hours, she cowered in fear as fighters dressed in military-style uniforms and desert camouflage roamed the streets of the neighbourhood. A heavy machine gun was mounted on a military vehicle just beneath her balcony window.

"Jihad against Druze" and "we are going to kill you, Druze," the men were shouting.

She did not know who the men were - extremists, government security forces, or someone else entirely - but the message was clear: as a Druze, she was not safe.

The Druze - a community with its own unique practices and beliefs, whose faith began as an off-shoot of Shia Islam - have historically occupied a precarious position in Syria's political order.

Under former President Bashar al-Assad, many Druze maintained a quiet loyalty to the state, hoping that alignment with it would protect them from the sectarian bloodshed that consumed other parts of Syria during the 13-year-long civil war.

Many Druze took to the streets during the uprising, especially in the latter years. But, seeking to portray himself as defending Syria's minorities against Islamist extremism, Assad avoided using the kind of iron first against Druze protesters which he did in other cities that revolted against his rule.

They operated their own militia which defended their areas against attacks by Sunni Muslim extremist groups who considered Druze heretics, while they were left alone by pro-Assad forces.

But with Assad toppled by Sunni Islamist-led rebels who have formed the interim government, that unspoken pact has frayed, and Druze are now worried about being isolated and targeted in post-war Syria.

Recent attacks on Druze communities by Islamist militias loosely affiliated with the government in Damascus have fuelled growing distrust towards the state.

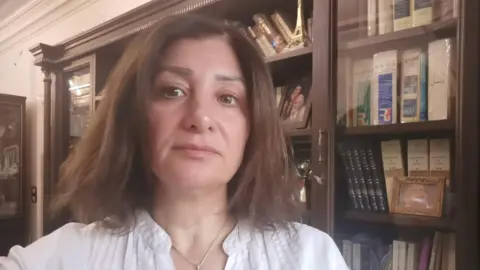

Lama witnessed the outbreak of violent attacks against Druze in Ashrafiyat Sahnaya

It started in late April with a leaked audio recording that allegedly featured a Druze religious leader insulting the Prophet Muhammad. Although the leader denied it was his voice, and Syria's interior ministry later confirmed the recording was fake, the damage had been done.

A video of a student at the University of Homs, in central Syria, went viral, with him calling on Muslims to take revenge immediately against Druze, sparking sectarian violence in communities across the country.

The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a UK-based monitoring group, said at least 137 people - 17 civilians, 89 Druze fighters and 32 members of the security forces - were killed in several days of fighting in Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, the southern Damascus suburb of Jaramana, and in an ambush on the Suweida-Damascus highway.

The Syrian government said the security forces' operation in Ashrafiyat Sahnaya was carried out to restore security and stability, and that it was in response to attacks on its own personnel where 16 of them were killed.

Lama Zahereddine, a pharmacy student at Damascus University, was just weeks away from completing her degree when the violence reached her village. What began as distant shelling turned into a direct assault - gunfire, mortars, and chaos tearing through her neighbourhood.

Her uncle arrived in a small bus, urging the women and children to flee under fire while the men stayed behind with nothing more than light arms. "The attackers had heavy machine guns and mortars," Lama recalled. "Our men had nothing to match that."

The violence did not stop at her village. At Lama's university, dorm rooms were stormed and students were beaten with chains.

In one case, a student was stabbed after simply being asked if he was Druze.

This university student, also named Lama, says her dorms were stormed and Druze students were beaten

"They [the instigators] told us we left our universities by choice," she said. "But how could I stay? I was five classes and one graduation project away from my degree. Why would I abandon that if it wasn't serious?"

Like many Druze, Lama's fear is not just of physical attacks – it is of what she sees as a state that has failed to offer protection.

"The government says these were unaffiliated outlaws. Fine. But when are they going to be held accountable?" she asked.

Her trust was further shaken by classmates who mocked her plight, including one who replied with a laughing emoji to her post about fleeing her village.

"You never know how people really see you," she said quietly. "I don't know who to trust anymore."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Druze volunteers were brought in to help protect their community during the attacks

While no-one is sure who the attackers pledged their allegiance to, one thing is clear: many Druze are worried that Syria is drifting toward an intolerant Sunni-dominated order with little space for religious minorities like themselves.

"We don't feel safe with these people," Hadi Abou Hassoun told the BBC.

He was one of the Druze men from Suweida called in to protect Ashrafiyat Sahnaya on the day Lama was hiding in her bathroom.

His convoy was ambushed by armed groups using mortars and drones. Hadi was shot in the back, piercing his lung and breaking several ribs.

It's a far cry from the inclusive Syria he had in mind under new leadership.

"Their ideology is religious, not based on law or the state. And when someone acts out of religious or sectarian hate, they don't represent us," Hadi said.

"What represents us is the law and the state. The law is what protects everyone…I want protection from the law."

The Syrian government has repeatedly stressed the sovereignty and unity of all Syrian territories and denominations of Syrian society, including the Druze.

Hadi's lung was pierced by a bullet fired by an armed group that ambushed his volunteer group

Though clashes and attacks have since subsided, faith in the government's ability to protect minorities has diminished.

During the days of the fighting, Israel carried out air strikes around the Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, claiming it was targeting "operatives" attacking Druze to protect the minority group.

It also struck an area near the Syrian presidential palace, saying that it would "not allow the deployment of forces south of Damascus or any threat to the Druze community". Israel itself has a large number of Druze citizens in the country and living in the Israeli-occupied Syrian Golan Heights.

Back in Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, Lama al-Hassanieh said the atmosphere had shifted - it was "calmer, but cautious".

She sees neighbours again, but wariness lingers.

"Trust has been broken. There are people in the town now who don't belong, who came during the war. It's hard to know who's who anymore."

Trust in the government remains thin.

"They say they're working toward protecting all Syrians. But where are the real steps? Where is the justice?" Lama asked.

"I don't want to be called a minority. We are Syrians. All we ask for is the same rights - and for those who attacked us to be held accountable."

7 hours ago

12

7 hours ago

12

English (US) ·

English (US) ·