ARTICLE AD BOX

Bushra MohamedBBC World Service

Corbis/Getty Images

Corbis/Getty Images

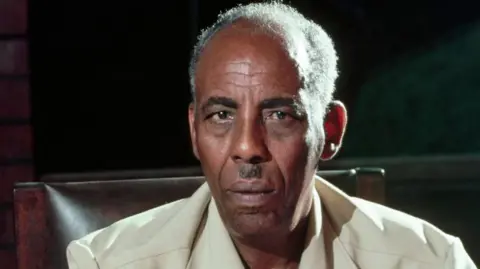

Siad Barre died in exile in Nigeria four years after fleeing Somalia

Exactly 31 years ago to the day, two Kenyan pilots, Hussein Mohamed Anshuur and Mohamed Adan, received an unexpected visitor at their office at Wilson Airport near the capital, Nairobi.

It was a Nigerian diplomat, who drew them into a sensitive and secretive mission to fly the body of Somalia's former ruler Siad Barre back to his homeland for burial following his death in exile in Nigeria at the age of 80.

Anshuur, previously a captain in the Kenyan Air Force, and Adan are partners in Bluebird Aviation, one of Kenya's largest private airlines that they had set up a few years earlier.

Speaking to the media for the first time about the mission, Anshuur told the BBC that the Nigerian diplomat came "straight to the point", asking him and Hussein "to charter an aircraft and secretly transport the body" from Nigeria's main city of Lagos, to Barre's hometown of Garbaharey in southern Somalia for burial, on the other side of Africa, a distance of some 4,300 km (2,700 miles).

Anshuur said they were stunned at the request: "We knew immediately this wasn't a normal charter."

Barre had fled Somalia on 28 January 1991 after being overthrown by militia forces, so returning his body was politically fraught, involving multiple governments, fragile regional relations and the risk of a diplomatic fallout.

Anshuur said they were fearful of the possible repercussions as the diplomat asked for the flight to be organised outside normal procedures.

"If the Kenyan authorities found out, it could have caused serious problems," Anshuur said.

The pilots spent the rest of the day debating whether to accept the request, carefully weighing the risks, particularly if the Kenyan government, then led by President Daniel arap Moi, discovered what they were planning to do.

Barre seized power in a bloodless coup in 1969. His supporters saw him as a pan-Africanist, who supported causes such as the campaign against the racist system of apartheid in South Africa.

To his critics, he was a dictator who oversaw numerous human rights abuses until he was driven from power.

Barre initially fled to Kenya, but Moi's government came under intense pressure from parliament and rights groups for hosting him. Barre was then given political asylum by Nigeria, then under military ruler Gen Ibrahim Babangida, and lived in Lagos until he died of a diabetes-related illness.

Given the sensitivity of the mission, the pilots asked the Nigerian diplomat to give them one more day to think about his request. The financial offer was lucrative - they didn't want to reveal the exact amount - but the risks were considerable.

"We first advised him to use a Nigerian Air Force aircraft, but he refused," Anshuur recalled. "He said that the operation was too sensitive and that the Kenyan government must not be informed."

Also speaking to the media for the first time about the mission, the former Somali ruler's son, Ayaanle Mohamed Siad Barre, told the BBC that "the secrecy wasn't about hiding anything illegal".

He explained that Islamic tradition requires a burial to take place as soon as possible, and therefore normal procedures were circumvented, though some governments were aware of the plan.

"Time was against us," he said. "If we had gone through all the paperwork, it would have delayed the burial."

He said he was told by Nigerian officials that Garbaharey's runway was "too small" for a military aircraft.

"That's why Bluebird Aviation was contacted," Barre's son told the BBC.

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty Images

Barre fled Somalia on 28 January 1991 after being overthrown by militia forces

The pilots had no contact with Barre's family at the time, and relayed their decision to the Nigerian diplomat, Anshuur said, on 10 January 1995.

"It wasn't an easy choice," Anshuur recalled. "But we felt the responsibility to execute the trip."

This was not their first connection to the former president.

When Barre and his family fled the capital Mogadishu, he arrived in Burdubo, a town in the same region as Garbaharey.

During that period, the pilots had flown essential supplies - including food, medicine and other basic necessities - to Burdubo for the Barre family.

But before embarking on the journey with Barre's body, the pilots demanded guarantees from the Nigerian government.

"That if anything goes wrong politically, Nigeria must take responsibility," Anshuur said. "And we wanted two embassy officials on board."

Nigeria agreed. The pilots then designed a plan to ensure their mission remained a secret - and succeeded.

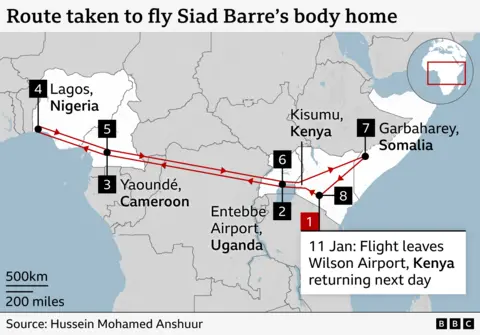

Just after 03:00 on 11 January, Anshuur said their small plane, a Beechcraft King Air B200, took off from Wilson Airport.

Hussein Mohamed Anshuur

Hussein Mohamed Anshuur

This Bluebird plane is similar to the one in which Siad Barre's body was flown

The pilots filed a flight manifest listing Kisumu, a lakeside city in western Kenya, as their destination.

"That was only on paper," Anshuur said. "When we got close to Kisumu, we switched off the radar and diverted to Entebbe in Uganda."

At the time, radar coverage across much of the region was limited, a gap the pilots knew they could exploit.

Upon landing in Entebbe, the pilots told airport authorities the aircraft had arrived from Kisumu. The two Nigerian officials on board were instructed to remain silent and not to disembark.

The plane was refuelled, and Yaoundé in Cameroon, was declared as the next destination, where Nigerian diplomats helping to coordinate the operation were waiting, Anshuur told the BBC

After a brief stop, the aircraft continued to Lagos. Before entering Nigerian airspace, the Nigerian government instructed the pilots to use a Nigerian Air Force call sign "WT 001" to avoid any suspicion.

"That detail mattered," Anshuur said. "Without it, we might have been questioned."

They arrived at around 13:00 on 11 January in Lagos, where Barre's family was waiting.

After resting for the rest of the day, the pilots prepared for the final leg of the journey - taking Barre's body to Garbaharey in Somalia.

On 12 January 1995, his wooden casket was loaded on to the aircraft. The two Nigerian government officials were also on the flight, this time with six members of the family, including his son Ayaanle Mohamed Siad Barre.

From the pilots' perspective, secrecy remained essential.

"At no point did we tell airport authorities in Cameroon, Uganda or Kenya that we were carrying a body," Hussein said. "That was deliberate."

The aircraft retraced its route, stopping briefly in Yaoundé before flying to Entebbe, where it refuelled. The Ugandan authorities were told the final destination was Kisumu in western Kenya.

As they neared Kisumu, the pilots diverted, this time flying directly to Garbaharey.

Anshuur said after the casket was offloaded, he and his co-pilot attended the burial and then departed for Wilson Airport, with the two Nigerian officials on board.

Anshuur said this turned out to be "the most stressful" part of their entire trip.

"You think: 'This is where we could be stopped.'"

Fearing being caught, the pilots informed Wilson air traffic control that they were arriving from Mandera in north-eastern Kenya, giving the impression that it was a local flight.

"No-one asked questions," Anshuur said. "That's when we knew we were safe."

With that, the mission was over.

"Only afterwards did it really sink in what we had done," Anshuur told the BBC.

Asked whether he would do it again, he replied: "I am 65 years old now and no, I would not carry out a similar mission today because aviation technology has improved so much that there is now sufficient air traffic radar coverage within the African continent.

"It is virtually impossible to exploit the gaps in air traffic control that existed way back in 1995."

More BBC stories on Somalia:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

22 hours ago

3

22 hours ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·