ARTICLE AD BOX

Soutik BiswasIndia correspondent

BBC

BBC

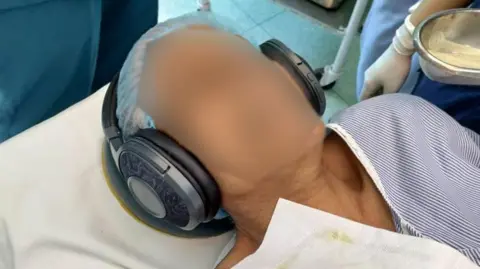

A patient with headphones playing music during surgery in a hospital in Delhi

Under the harsh lights of an operating theatre in the Indian capital, Delhi, a woman lies motionless as surgeons prepare to remove her gallbladder.

She is under general anaesthesia: unconscious, insensate and rendered completely still by a blend of drugs that induce deep sleep, block memory, blunt pain and temporarily paralyse her muscles.

Yet, amid the hum of monitors and the steady rhythm of the surgical team, a gentle stream of flute music plays through the headphones placed over her ears.

Even as the drugs silence much of her brain, its auditory pathway remains partly active. When she wakes up, she will regain consciousness more quickly and clearly because she required lower doses of anaesthetic drugs such as propofol and opioid painkillers than patients who heard no music.

That, at least, is what a new peer-reviewed study from Delhi's Maulana Azad Medical College suggests. The research, published in the journal Music and Medicine, offers some of the strongest evidence yet that music played during general anaesthesia can modestly but meaningfully reduce drug requirements and improve recovery.

The study focuses on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the standard keyhole operation to remove the gallbladder. The procedure is short - usually under an hour - and demands a particularly swift, "clear-headed" recovery.

To understand why the researchers turned to music, it helps to decode the modern practice of anaesthesia.

"Our aim is early discharge after surgery," says Dr Farah Husain, senior specialist in anaesthesia and certified music therapist for the study. "Patients need to wake up clear-headed, alert and oriented, and ideally pain-free. With better pain management, the stress response is curtailed."

Achieving that requires a carefully balanced mix of five or six drugs that together keep the patient asleep, block pain, prevent memory of the surgery and relax the muscles.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Patients need to wake up clear-headed and ideally pain-free after surgery

In procedures like laparoscopic gallbladder removal, anaesthesiologists now often supplement this drug regimen with regional "blocks" - ultrasound-guided injections that numb nerves in the abdominal wall.

"General anaesthesia plus blocks is the norm," says Dr Tanvi Goel, primary investigator and a former senior resident of Maulana Azad Medical College. "We've been doing this for decades."

But the body does not take to surgery easily. Even under anaesthesia, it reacts: heart rate rises, hormones surge, blood pressure spikes. Reducing and managing this cascade is one of the central goals of modern surgical care. Dr Husain explains that the stress response can slow recovery and worsen inflammation, highlighting why careful management is so important.

The stress starts even before the first cut, with intubation - the insertion of a breathing tube into the windpipe.

To do this, the anaesthesiologist uses a laryngoscope to lift the tongue and soft tissues at the base of the throat, obtain a clear view of the vocal cords, and guide the tube into the trachea. It's a routine step in general anaesthesia that keeps the airway open and allows precise control of the patient's breathing while they are unconscious.

"The laryngoscopy and intubation are considered the most stressful response during general anaesthesia," says Dr Sonia Wadhawan, director-professor of anaesthesia and intensive care at Maulana Azad Medical College and supervisor of the study.

"Although the patient is unconscious and will remember nothing, their body still reacts to the stress with changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and stress hormones."

To be sure, the drugs have evolved. The old ether masks have vanished. In their place are intravenous agents - most notably propofol, the hypnotic made infamous by Michael Jackson's death but prized in operating theatres for its rapid onset and clean recovery. "Propofol acts within about 12 seconds," notes Dr Goel. "We prefer it for short surgeries like laparoscopic cholecystectomy because it avoids the 'hangover' caused by inhalational gases."

The team of researchers wanted to know whether music could reduce how much propofol and fentanyl (an opioid painkiller) patients required. Less drugs means faster awakening, steadier vital signs and reduced side effects.

So they designed a study. A pilot involving eight patients led to a full 11-month trial of 56 adults, aged roughly 20 to 45, randomly assigned to two groups. All received the same five-drug regimen: a drug that prevents nausea and vomiting, a sedative, fentanyl, propofol and a muscle relaxant. Both groups wore noise-cancelling headphones - but only one heard music.

"We asked patients to select from two calming instrumental pieces - soft flute or piano," says Dr Husain. "The unconscious mind still has areas that remain active. Even if the music isn't explicitly recalled, implicit awareness can lead to beneficial effects."

A pilot involving eight patients led to a full trial of 56 adults randomly assigned to two groups

The results were striking.

Patients exposed to music required lower doses of propofol and fentanyl. They experienced smoother recoveries, lower cortisol or stress-hormone levels and a much better control of blood pressure during the surgery. "Since the ability to hear remains intact under anaesthesia," the researchers write, "music can still shape the brain's internal state."

Clearly, music seemed to quieten the internal storm. "The auditory pathway remains active even when you're unconscious," says Dr Wadhawan. "You may not remember the music, but the brain registers it."

The idea that the mind behind the anaesthetic veil is not entirely silent has long intrigued scientists. Rare cases of "intraoperative awareness" show patients recalling fragments of operating-room conversation.

If the brain is capable of picking up and remembering stressful experiences during surgery - even when a patient is unconscious - then it might also be able to register positive or comforting experiences, like music, even without conscious memory.

"We're only beginning to explore how the unconscious mind responds to non-pharmacological interventions like music," says Dr Husain. "It's a way of humanising the operating room."

Music therapy is not new to medicine; it has long been used in psychiatry, stroke rehabilitation and palliative care. But its entry into the intensely technical, machine-governed world of anaesthesia marks a quiet shift.

If such a simple intervention can reduce drug use and speed recovery - even modestly - it could reshape how hospitals think about surgical wellbeing.

As the research team prepares its next study exploring music-aided sedation, building on earlier findings, one truth is already humming through the data: even when the body is still and the mind asleep, it appears a few gentle notes can help the healing begin.

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·