ARTICLE AD BOX

Getty Images

Getty Images

Anjel Chakma, 24, died in a hospital in Dehradun, 17 days after being attacked by a group of men

The northern Indian city of Dehradun, located in the Himalayan foothills, was shaken by a violent incident weeks ago.

Brothers Anjel and Michael Chakma - students who had migrated more than 1,500 miles from the north-eastern state of Tripura for studies - had gone to a market on 9 December when they were confronted by a group of men, who allegedly abused them with racial slurs, their father Tarun Chakma told the BBC.

When the brothers protested, they were attacked. Michael Chakma was allegedly struck on the head with a metal bracelet, while Anjel Chakma suffered stab wounds. Michael has recovered but Anjel died 17 days later in hospital, he says.

Police in Uttarakhand state (whose capital is Dehradun) have arrested five people in connection with the incident, but they have denied that the attack was racially motivated - a claim that Chakma's family strongly disputes.

The incident, which has triggered protests in several cities, has put the spotlight on allegations of racism faced by people from India's north-eastern states when they move to larger cities for education or work. They say they are often mocked over their appearance, questioned about nationality and harassed in public spaces and workplaces.

For many, the discrimination extends beyond abuse to everyday barriers that shape where and how they live. People from the region report difficulty renting accommodation, with landlords refusing tenants because of their appearance, food habits or stereotypes.

Such pressures have led many north-eastern migrants in large cities to cluster in specific neighbourhoods, offering safety, mutual support and cultural familiarity far from home.

But while many say they learn to endure everyday prejudices to build lives elsewhere in the country, violent crimes such as Anjel Chakma's killing are deeply unsettling. They reinforce fears about personal safety and a sense of vulnerability, they say.

Getty Images

Getty Images

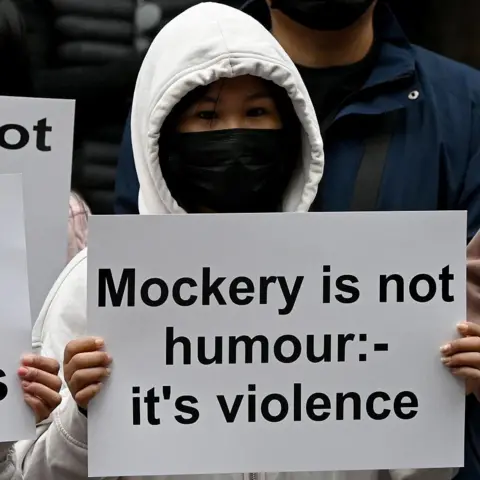

Protesters demand an anti-racism law in India in the aftermath of Anjel Chakma's killing

India has seen many high-profile cases of racial violence involving people from the north-eastern region over the last several years.

The killing of Nido Tania in 2014 became a national flashpoint, prompting protests and widespread debate about racism after the 20-year-old student from Arunachal Pradesh state was beaten to death in Delhi following taunts about his appearance.

But activists say it did not mark an end to such violence.

In 2016, a 26-year-old student from the region was beaten up in Pune. A year later, another student was racially abused and assaulted by his landlord in Bengaluru.

Rights groups say there are many such incidents that do not grab national attention.

"Unfortunately, the racism faced by people from the north-east tends to be highlighted only when something extremely violent happens," said Suhas Chakma, director of the Delhi-based Rights and Risks Analysis Group.

The federal government in its annual crime reports does not maintain separate data for racial violence.

For Ambika Phonglo from the north-eastern Assam state, who lives and works in the capital, Anjel Chakma's killing has been deeply unsettling. "Our facial features like narrow eyes and flat noses make us easy targets of racism," she says.

Phonglo recalls being subjected to racial name-calling by colleagues during a workplace discussion a few years ago. "You face it and learn to move on," she says, "but not without carrying a heavy burden of trauma."

Mary Wahlang, from neighbouring state of Meghalaya, said she decided to return home after college in the southern state of Karnataka, abandoning plans to seek work in larger cities, after repeated racial name-calling by classmates.

"Over time I realised that some people used these slurs without understanding they were racial or hurtful, while others did so despite knowing the consequences," she says.

Such experiences, activists say, are not isolated, with many from north-eastern states describing racial taunts and everyday discrimination as a routine part of life in workplaces, campuses and public spaces across the country's major cities.

While awareness about the north-eastern region and the racism people from there face have improved over the years, casual racism persists, they say.

"How do we look Indian enough? Sadly, there are no clear answers," says Alana Golmei, member of a monitoring committee set up by the federal government in 2018 in the wake of increasing complaints of racial violence in Indian cities.

She says that dismissing such attacks as isolated incidents unrelated to racism only deepens the problem. "One has to first accept and acknowledge the issue to begin addressing it," Golmei told the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty Images

India has seen many cases of violence involving people from the north-eastern states

The killing of Anjel Chakma has renewed calls for a specific anti-racism law. Several student and civil society groups have issued open letters demanding legal reform.

After Nido Tania's death in 2014, the Indian government set up a committee to examine discrimination faced by people from the north-east living outside of the region.

The panel submitted its report to the home ministry the same year, acknowledging widespread racism and recommending several measures, including a standalone anti-racism law, fast-track investigations and institutional safeguards.

But activists say little has changed since. No specific anti-racism legislation has been enacted, and many of the recommendations remain only partially implemented.

The BBC has sought clarification from the federal government, but they are yet to respond.

The renewed demands over an anti-racism law have revived a broader debate over whether legislation can address prejudice, often seen as rooted in social behaviour.

Experts and activists such as Chakma and Golmei argue that it can.

They cite laws criminalising dowry and caste-based atrocities, arguing that while these haven't ended abuse, they have empowered victims and raised awareness.

"An anti-racism law could empower victims, improve reporting and place racial abuse clearly within the scope of criminal accountability," Golmei said.

Meanwhile in Tripura, Tarun Chakma mourns his elder son while facing uncertainty over his younger one: Michael, a final-year sociology student, is expected to return to Dehradun to complete his studies.

While family members have urged caution, Tarun Chakma says he is torn between fear for his son's safety and the belief that abandoning his education would amount to another loss.

"At the end of the day, higher education for a better future was the reason for which we had sent our sons so far away from home," he says.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter and Facebook.

21 hours ago

4

21 hours ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·