ARTICLE AD BOX

Steve RosenbergRussia editor, for Panorama

BBC

BBC

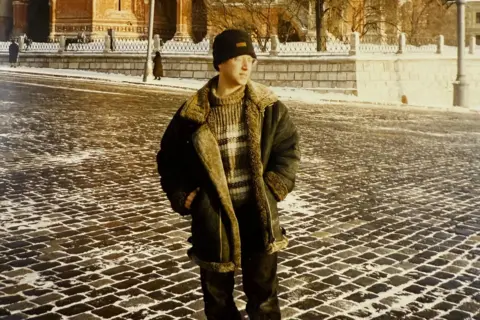

Both Steve Rosenberg and BBC producer Ben Tavener (left) can face extra scrutiny on their travels in and out of Russia

On his Russian TV show, a famous presenter takes aim and unleashes a tirade against the UK.

I'm just glad it's not his finger on the nuclear button.

"We still haven't destroyed London or Birmingham," barks Vladimir Solovyov. "We haven't wiped all this British scum from the face of the earth."

"We haven't kicked out the goddamned BBC with that Steve Rotten-berg. He walks around looking like a defecating squirrel…he's a conscious enemy of our country!"

Welcome to my world: the world of a BBC correspondent in Russia.

It's a world we offer a glimpse into in Our Man in Moscow. The film for BBC Panorama charts a year in the life of the BBC Moscow bureau, as the Kremlin continues to wage war on Ukraine, tighten the screws at home and build a relationship with President Trump.

The squirrel barb doesn't bother me. Squirrels are cute. And they have a thick skin - something a foreign correspondent needs here.

But "enemy of Russia"? That hurts.

Solovyov Live, VGTRK

Solovyov Live, VGTRK

Vladimir Solovyov has referred to Steve Rosenberg as "Steve Rotten-berg" and said he looks like a "defecating squirrel"

I have spent more than thirty years living and working in Moscow. As a young man I fell in love with the language, literature and music of Russia. At university in Leeds, I ran a choir that performed Russian folk classics. For one concert I wrote a song in Russian about a snowman who put on so many clothes that he melted.

Like that snowman, the Russia I knew seemed to melt away in February 2022. With its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the world's largest country had embarked on the darkest of paths. President Putin's "special military operation" would become the deadliest war in Europe since World War Two.

Looking back, this hadn't come out of nowhere: Russia had annexed Crimea from Ukraine back in 2014; it had already been accused of funding, fuelling and orchestrating an armed uprising in eastern Ukraine. Relations with the West were becoming increasingly strained.

Still, the full-scale invasion was a watershed moment.

In the days that followed, repressive new laws were adopted here to silence dissent and punish criticism of the authorities. BBC platforms were blocked. Suddenly reporting from Russia felt like walking a tightrope over a legal minefield. The challenge: to report accurately and honestly about what was happening without falling off the highwire.

In 2023 the arrest of a Wall Street Journal reporter showed that a foreign passport was no "keep out of jail" card. Evan Gershkovich, a US citizen, was convicted on espionage charges. He would spend sixteen months behind bars. He, his employer and the US authorities denounced the case as a sham.

In the BBC's Moscow office we're a much smaller team now. Together we try to navigate the daily challenges of reporting the Russia story.

Producer Ben Tavener and I often face "additional checks" flying in and out of Russia. Reporters from countries labelled "unfriendly" by the Kremlin (that includes the UK) are no longer issued one-year permits. Our journalist visas and accreditation cards require renewal every three months.

Many contributors who used to speak to us are now reluctant to do so. Probably they think that at a time of heightened international tension being associated with the BBC isn't worth the risk.

Steve Rosenberg

Steve Rosenberg

Steve Rosenberg first visited Moscow in the days of the Soviet Union

Yet along with other Western broadcasters that have retained a presence in Russia we have still been receiving invitations to Kremlin events.

And sometimes I get the chance to quiz President Putin.

Even a single question and answer at a press conference can provide valuable insight into the Russian president's thinking.

Vladimir Putin is driven by resentment of the West: over Nato's enlargement eastwards, and what he perceives as years of disrespect for Russia from Western leaders. His critics accuse him of imperialist designs, of trying to reforge Russia's sphere of influence.

"Will there be new 'special military operations'?" I asked President Putin last December as a part of a wider question about his plans.

"There won't be any operations if you treat us with respect. If you respect our interests…" the Kremlin leader replied.

Which raises the question: if Vladimir Putin concludes that Russia's interests have not been respected, what then?

Watch: Putin tells BBC Western leaders deceived Russia

With Donald Trump back in the White House, Moscow feels that Washington is paying it more respect. At the Alaska summit last August, America's president rolled out the red carpet for Russia's leader. By inviting him to Anchorage Donald Trump had brought Vladimir Putin in from the cold, even though the summit failed to end Russia's war on Ukraine.

It hasn't all gone Moscow's way. Venezuela's president Nicolás Maduro, captured recently by US troops, was Russia's ally. Then America seized an oil tanker in the Atlantic: it was sailing under a Russian flag.

Still, it's striking how little the Kremlin has criticised America over the last 12 months. Moscow seems to believe good relations with the Trump administration will help it end the Ukraine war on terms beneficial to the Kremlin.

So now most of the anti-Western rhetoric in the Russian state media is directed, not at America, but at the European Union and the UK.

In 1997 I was invited onto "The White Parrot Club", a popular Russian TV comedy show starring a white parrot called Arkasha. Russian celebrities sat around in a bar telling each other British jokes and speaking lovingly of the UK.

"In 1944 I was on the frontline in World War Two," recalled film legend Yuri Nikulin. "I remember how Britain and the Allies opened the Second Front. That helped us so much."

The Parrot Club fraternity invited me to "sing something British". I sat at the piano and sang about "Daisy! Daisy!" and "a bicycle made for two".

WATCH: Steve Rosenberg plays the piano on Russian TV in 1997

Sitting in that Moscow bar, it felt as if Britain couldn't be closer to Russian hearts. I remember thinking that Russia and the West were on that "bicycle made for two", and that Cold War-style confrontation was all in the past.

In thirty years, we've gone from "white parrots" to "defecating squirrels".

Far worse, we've swung from hopes of East-West friendship to a four-year-long war in Europe that has been devastating, first and foremost, for Ukraine.

How this war ends will affect not only Ukraine's future and that of Russia, but the future of Europe, too.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Moscow's Red Square has played host to fervent rallies of support for Vladimir Putin

Over the last four years there have been moments that have shocked me. I'll never forget my conversation with Vera at a highly choreographed pro-Putin rally in 2022. I'd asked her if she had a son. She had.

"Aren't you worried," I asked, "that he might be drafted into the army and sent to Ukraine?"

"I'd rather my son was killed fighting in Ukraine than see him getting up to mischief at home," Vera replied. "Look how many young men here have no job and spend their time getting drunk."

There have been more pleasant encounters, too. A few days after TV host Vladimir Solovyov labelled me an "enemy of Russia," several Muscovites came up to me to shake my hand and ask for selfies.

It's like Russia's national symbol: the double-headed eagle. One head is growling and calling you a "defecating squirrel."

The other is saying: "Thanks for being here."

More from Russia Editor Steve Rosenberg

6 hours ago

10

6 hours ago

10

English (US) ·

English (US) ·